Sat 29 May 2021:

Before the British allowed European Zionists to colonise Palestine, its chief idealogue, Theodor Herzl, attempted to buy the land from the Ottomans.

Long before the controversial Balfour Declaration set in motion the colonisation of Palestine at the behest of the British Empire, one of the leading founders of Zionism, Theodor Herzl, appealed to the Ottoman state for a Jewish country.

Palestine and its people were a constituent part of the Ottoman lands linking the Sublime Port in Istanbul to the wider domains, encompassing Islam’s three holiest sites of Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem.

Ottoman Sultans were also the caliphs of Islam from which they derived their authority by holding in their possession the holiest places of the Muslim world. But the Ottoman state also had a more worldly problem – debt, and lots of it.

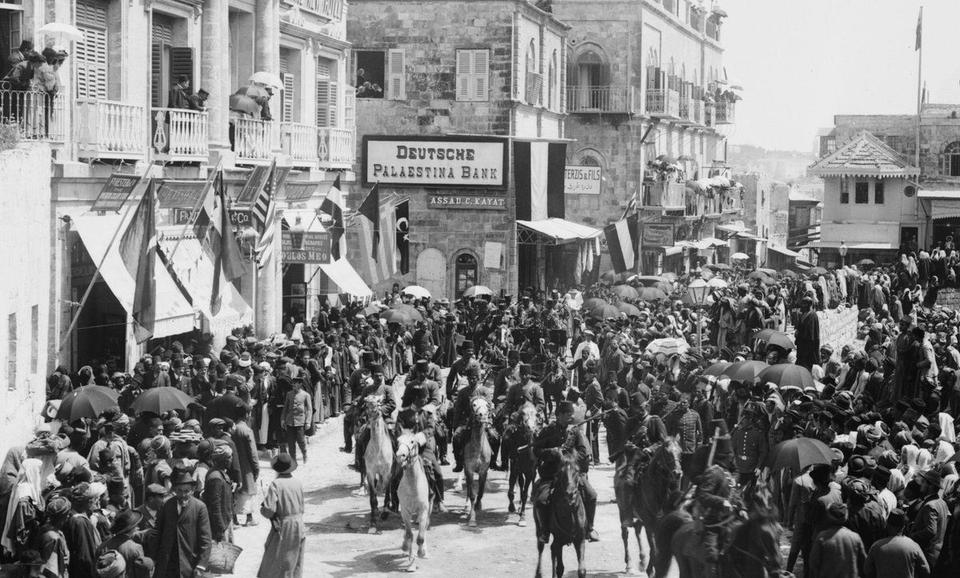

In 1896, Herzl sensed a real-estate opportunity and came to Istanbul with a deal he thought the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II couldn’t turn down.

The Ottoman state was creaking under an accumulated debt burden which by the late 19th century stood at a present-day value of $11.6 billion.

The debt was controlled through a vehicle called the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, which represented European powers such as the British, French, Germans, Austrians, Italians and the Dutch. This gave European colonial powers a level of control inside the Ottoman state that would ultimately prove to be its undoing.

Cash for land

According to one historical account, Herzl offered to pay £20 million, which is around $2.2 billion in today’s currency, to the Ottoman Sultan to issue a charter for Jews to colonise Palestine.

That kind of money would have shaved around 20 percent of the Ottomans’ debt burden. It’s reported that Herzel exclaimed that “without the help of the Zionists, the Turkish economy would not stand a chance of recovery.”

Herzl’s interlocutors with the Ottoman Sultan at the time, Philip de Newlinski and Arminius Vambery, were sceptical that Jerusalem as the third holiest place in Islam would simply be sold, no matter how precarious Ottoman finances were.

They were right. Sultan Abdul Hamid II refused the offer outright in 1896, telling Newlinski, “if Mr Herzl is as much your friend as you are mine, then advise him not to take another step in this matter. I cannot sell even a foot of land, for it does not belong to me but to my people. My people have won this Empire by fighting for it with their blood and have fertilised it with their blood. We will again cover it with our blood before we allow it to be wrested away from us.”

The Sultan’s words were prophetic. Yet while the conflict is sometimes portrayed as an ancient one going back more than 1000 years, its roots are distinctly in the late 19th century.

The idea of Zionism was underpinned by the notion that Jews could be transferred from Europe to Palestine as a means of ridding what Europe called its ‘Jewish problem’.

Many non-Jews and even anti-Semites supported the idea of European Jews being relocated to the Middle East, which would have entailed the disposition of native Palestinians from their homes. Some Jews like Herzl, although not all, bought into this idea which imbued the Zionist idea from its inception as a colonial project.

The historian Louis Fishman in his book ‘Jews and Palestinians in the Late Ottoman Era’, made the case that the “colonial Jewish project developed within an Ottoman context.”

But Jewish migrations to Palestine also developed against a backdrop of rabid European led anti-Semitism, which Herzl and his Zionist contemporaries realised would never abate – and he was right.

Ottoman Jews vs European Jews

By the turn of the of the 19th century, as ideas of Zionism were spreading amongst some Ottoman Jews, distinct and important differences emerged with their European Zionist counterparts.

In the book “Late Ottoman Palestine: The Period of Young Turk Rule”, the historians Eyal Geno and Yuval Ben-Bassat noted that for Ottoman Jews, “Zionism was a cultural form of nationalism, an emerging identity which did not clash with their loyalty to the Ottoman state and which did not require moving to the far-off lands of Ottoman Palestine.”

European Jewish Zionists emerged from the context of European global colonisation. If European settlers could ethnically cleanse the indigenous peoples in America or Australia and create a new state on the supremacy of one race, why not European Jews?

Ottoman Jews, on the other hand, had been welcomed into the Ottoman domains by Sultan Bayezid II. The Ottoman state sent ships to help Jews flee from the Spanish Inquisition in 1492.

For many Ottoman Jews, being part of the Ottoman state had allowed them to rise to positions of prominence, and over the centuries, their day to day life would have been free of the pogroms European Jews had to endure.

The Jewish people in the Ottoman state

When Herzl finally met Sultan Abdul Hamid II face to face in 1901, he suggested that Jewish financiers could set up a company in Istanbul and, over time, purchase Ottoman debt from European powers.

In return, some lands in Palestine could be given autonomy and become a destination for Jewish migration. Herzl’s idea was a compromise on independence, however, while Abdul Hamid II was keen on the idea of consolidating foreign debts within the Empire, he maintained that it was a separate deal that would not be linked to the Jewish colonisation of Palestine.

European Jewish migration to Palestine, a trickle at the time, was nonetheless causing tensions with the indigenous Palestinian inhabitants.

The Ottomans, however, struggling to keep its domains in the Balkans and faced with an internal political upheaval as a result of a constitutional crisis, often found itself putting out fires that threatened to overwhelm the Empire.

Yet even against this backdrop, when the question of Jewish migration surfaced in the Ottoman parliament, the Ottoman Jewish parliamentarian Nissim Matzliah made clear that “if Zionism is indeed harmful to the State, then without question my loyalty lies with the State.”

However, the Ottoman state increasingly viewed European Zionism and its ambitions on its domains as part of another colonial attempt to carve up its lands.

In a detailed report to Istanbul, the Ottoman Ambassador to Berlin, Ahmet Tewfik Pasha, wrote, “we must have no illusions about Zionism” the aim he added was nothing short of “formation of a great Jewish State in Palestine, which would also spread towards the neighbouring countries.”

In his memoirs, Sultan Abdul Hamid II remarked that Herzl had attempted to deceive the state about their ultimate intentions over the land. Ottoman suspicions were later confirmed as Herzl, realising that appealing to Istanbul would not get results, ended up allying with the British – and the rest is history.