Social media has been awash with fake images of a stylish Pope Francis, Elon Musk protesting in New York and Donald Trump resisting arrest.

uch AI-generated images and videos, or deepfakes, have become increasingly accessible due to advances in artificial intelligence. As more sophisticated fabricated images spread, it will become increasingly difficult for users to differentiate the real from the fake.

Deepfakes get their name from the technology used to create them: deep-learning neural networks. When unleashed on a dataset, these algorithms learn patterns and can replicate them in novel — and convincing — ways.

While this technology can be used for entertainment, it also has dark potential, raising social and ethical concerns.

Unlike simple stories or memes which differ little from propaganda techniques used by Nazi Germany and photo editing by Communist Russia, deepfakes have a high degree of realism. Their accessibility to the public and states could erode our sense of reality.

An AI-generated image of Pope Francis wearing a white puffer jacket went viral online, with users wondering if it was real.

Fake news anchor

Beyond the growing concern that AI-generated art threatens human art and artists, deepfakes can be used as the unchecked mouthpieces for organizations and states.

Leading the way, China’s state media has experimented with an AI news anchors, named Ren Xiaorong. Ren, although not the first AI news anchor developed by China, illustrates both the commitment to the technology and the incremental increases in realism.

Other countries such as Kuwait and Russia have also launched AI generated anchors.

When looking at these anchors, we might object that only the most naive viewer would mistake them for real humans, such as Russia’s first robotic news anchor. Yet, these technologies are still in their infancy. We cannot dismiss them.

WATCH: Kuwait debuts 1st AI-generated news presenter

"I am Fedha, the first broadcaster in Kuwait that operates using Artificial Intelligence at the Kuwait News Cooperation. What type of news are you most interested in? Let us hear your thoughts." pic.twitter.com/EaYXUNqxbb

— Middle East Monitor (@MiddleEastMnt) April 11, 2023

Fabricated news

China’s transparency in using AI-generated news anchors stands in contrast to Venezuela’s fabricated news coverage. Venezuelan state media presented favourable reports of the country’s progress, purportedly created by international English-language news outlets. However, the stories and anchors were fabricated.

The use of these videos in Venezuela is particularly troubling because they are used as external validation for the government’s activities. By claiming the video comes from outside of one’s country, it provides another source to bolster their claims.

Venezuela is not the only country to adopt these methods. Fabricated videos of Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy discussing surrender to Russia were also circulated during the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Fabricated images and videos are merely the tip of the deepfake iceberg. In 2021, Russia was accused of using deepfake image filters to simulate opponents during interviews with international politicians. The ability to mimic political figures and interact with others in real time is a truly disturbing development.

As these technologies become increasingly accessible to everyone, from harmless meme-makers and would-be social engineers, the boundaries of the real and imagined become progressively indistinguishable.

The proliferation of deepfakes foreshadow a post-truth world, defined by a fractured geopolitical landscape, opinion echo chambers and mutual distrust that can be exploited by governmental and non-governmental organizations.

Disinformation and believable fakes

The spread of disinformation requires that we understand how ideas, innovation or behaviour spread within a social network, referred to as social contagion.

Cognitive science is concerned with “information” — anything that reduces our uncertainty about the actual state of the world. Disinformation has the appearance of information, except uncertainty is reduced at the expense of accuracy.

Observations that disinformation spreads faster that facts likely stems from the fact that when a message is simple, it increases our confidence.

Disinformation spreads for a variety of reasons. It must appear close enough to the “truth” that it is believable. If a new “fact” is incompatible with what we know, we are inclined to reject it even if it is true. People don’t like the feeling of inconsistency and seek to resolve it. People will also ignore the structure and quality of an argument, and focus on the believability of its conclusion.

Deepfakes move us beyond text-based persuasion, because images make a message far more memorable — and persuasive — than abstract concepts alone. Its use in spreading disinformation is therefore far more concerning.

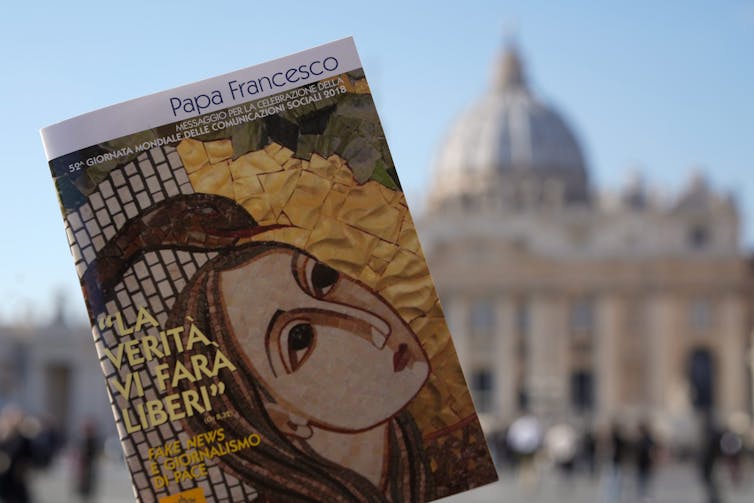

In 2018, Pope Francis published his annual social communications message, titled ‘The Truth Will Set You Free,’ after facing unprecedented bad press during his South American tour. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

The structure of the environment is also critical. People attend to available information, focusing on information that confirms their prior beliefs. By increasing the frequency of images, ideas and other media, we increase people’s confidence in their own knowledge and the illusion of consensus.

Social networks and contagion

While we look for credible sources of information — experts or peers — our memory stores information separately from its source. Over time, this failure of source monitoring results in our retrieval of information from memory without understanding its origin.

Through product placement and algorithms that control our exposure to media, marketers and governments have exploited these techniques for generations. Most recently, social media influencers have been paid to spread disinformation.

The introduction of AI will only accelerate this process by permitting tighter control of the information environment through dark patterns of design.

Legal, social and moral issues

Producing, managing and disseminating information grants people authority and power. When information ecosystems become flooded with disinformation, truth is debased.

The accusation of “fake news” has become a tactic used to discredit any argument. Deepfakes are variations on this theme. Social media users have already falsely claimed that real videos of U.S. President Joe Biden and former U.S. president Donald Trump are fake.

Social movements such as Black Lives Matter or claims about the treatment of the Uyghurs in China rely on the compelling qualities of videos.

Once we form a belief, it is difficult to counter. The time required for verification — especially if left to the user — allows disinformation to propagate. Private and public fact-checking websites can help. But they need legitimacy to foster trust.

Brazil provides a recent demonstration of such an attempt. After the government launched a verification website, critics accused it of pro-government bias. However, government officials noted that the site was not meant to replace private initiatives.

There is no simple solution to unmasking deepfakes. Rather than passive consumers of media, we must actively challenge our own beliefs.

The only way to combat harmful forms of artificial intelligence is to cultivate human intelligence.

![]()

Jordan Richard Schoenherr

Assistant Professor, Psychology, Concordia University

Dr. Jordan Richard Schoenherr is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology (Concordia University), an Adjunct Research Professor in the Department of Psychology and a member of the Institute for Data Science (Carleton University). He has also served as an Associate Editor for IEEE Transaction in Technology and Society. His primary areas of interest are learning and decision-making and metacognition with application in medical education, organizational behaviour (incivility, insider threat, and knowledge management), cybersecurity, and artificial intelligence (ethical AI and XAI).

A former postdoctoral fellow at the University of Ottawa’s Skills and Simulation Centre (uOSSC) and a visiting scholar at the US Military Academy’s (West Point) Army Cyber Institute. He has acted as a consultant for the Ombudsman, Integrity, and Resolution Office (Health Canada / PHAC), the Office of the Chief Scientist (Health Canada), and as an advisor at the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA). His focus has been on workplace incivility, scientific integrity, ethical models of cybersecurity, and education assessment and evaluation.

He is the author of Ethical Artificial Intelligence from Popular to Cognitive Science available from Taylor and Francis and a forthcoming co-edited volume Fundamentals and Frontiers of Medical Education and Decision-Making.

______________________________________________________________

FOLLOW INDEPENDENT PRESS:

WhatsApp CHANNEL

https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaAtNxX8fewmiFmN7N22

![]()

TWITTER (CLICK HERE)

https://twitter.com/IpIndependent

FACEBOOK (CLICK HERE)

https://web.facebook.com/ipindependent

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!